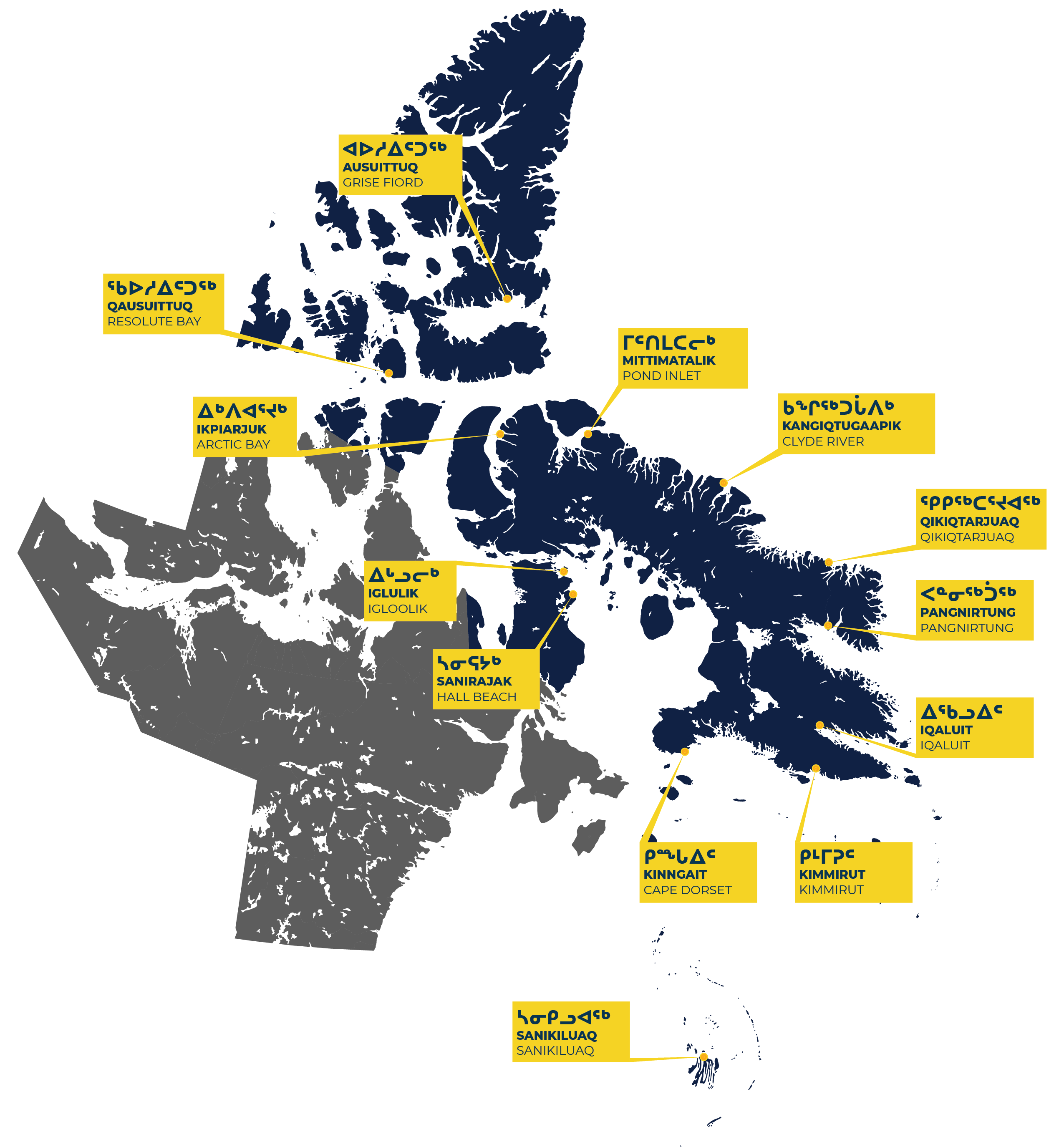

Communities

ᑭᓱᓕᕆᕙᓐᓂᕗᑦ

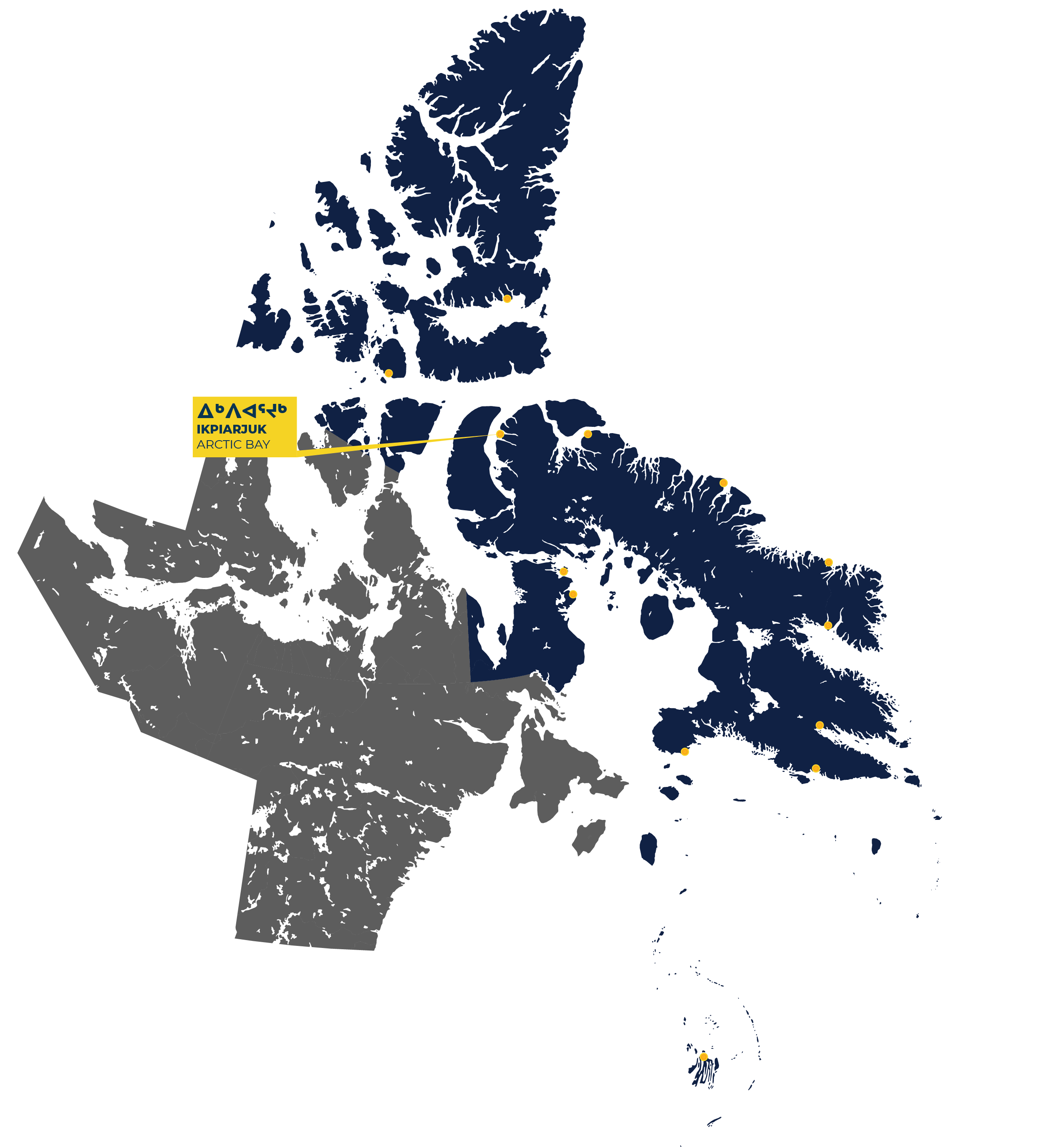

The Qikiqtani Region includes 13 communities from Grise Fiord, in the High Arctic, down to Sanikiluaq, on the Belcher Islands. Click the names below to learn more about each community.

Arctic Bay / Ikpiarjuk

994 Total Population

96% Inuit Population

93% Inuktitut Speaking

25.2 Average Age

38% Population with a high school diploma

Arctic Bay, or Ikpiarjuk, which means ‘pocket’, is nestled between tall hills and ocean at the entrance to Sirmilik National Park. The community is located on the north shore of Adams Sound, off the coast of Admiralty Inlet on northern Baffin Island.

The English name for the community references the whaling vessel Arctic that surveyed the area in 1872 under the command of Captain Williams Adams. In 1910-11 the Canadian government expedition ship, also named Arctic, was iced in over winter at Arctic Bay. The ship’s crew spelled out “Arctic Bay” in stone on the cliffs overlooking the entrance to the bay, which can still be seen today.

Today, the community is renowned for the quality of its whalebone and soapstone carvings, which often depict harvesting scenes and locally known animals and birds. Hiking, camping, and fishing are popular local activities that can be enjoyed in nearby Sirmilik National Park.

History

Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (Inuit traditional knowledge) and archaeological records show that Inuit have inhabited the area for over 2,000 years. The Inuit of this area were known as Tununirmiut, meaning “the people of a shaded or shadowy place” which references the mountainous landscape of the region. Abundant harvesting of seal, whale, narwhal, fish and other wildlife has long drawn these nomadic groups of Inuit to the area.

Arctic Bay was established as a community when the Hudson’s Bay Company set up a post in the area in 1936. At the same time, the federal government relocated several Inuit families to the Arctic Bay area from Kinngait, Pangnirtung, and Pond Inlet. In the 1950s the federal government lured Inuit to the community with promises of modern services. By the end of the 1960s the settlement included a school, hostel, 22 houses, and a small set of government offices.

In 1957 a large deposit of lead and zinc was discovered which resulted in the opening of the Nansivik mine in 1970. The mine was approximately 20km away from Arctic Bay and had a tremendous impact on the community and its economy. Opportunities for wage employment transformed the role of money, affecting Inuit harvesting practices and social structures. Nanisivik mine closed in 2002.

In March 2019, the Government of Canada issued a formal apology to Inuit for its actions on the Tuberculosis epidemic from the 1940s to 1960s. In August 2019, the Government of Canada formally acknowledged and apologized for its colonial actions and policies towards Inuit in the Qikiqtani Region between 1950 to 1975.

To learn more about the history of Inuit and the community of Arctic Bay, visit the Qikiqtani Truth Commission Community History.

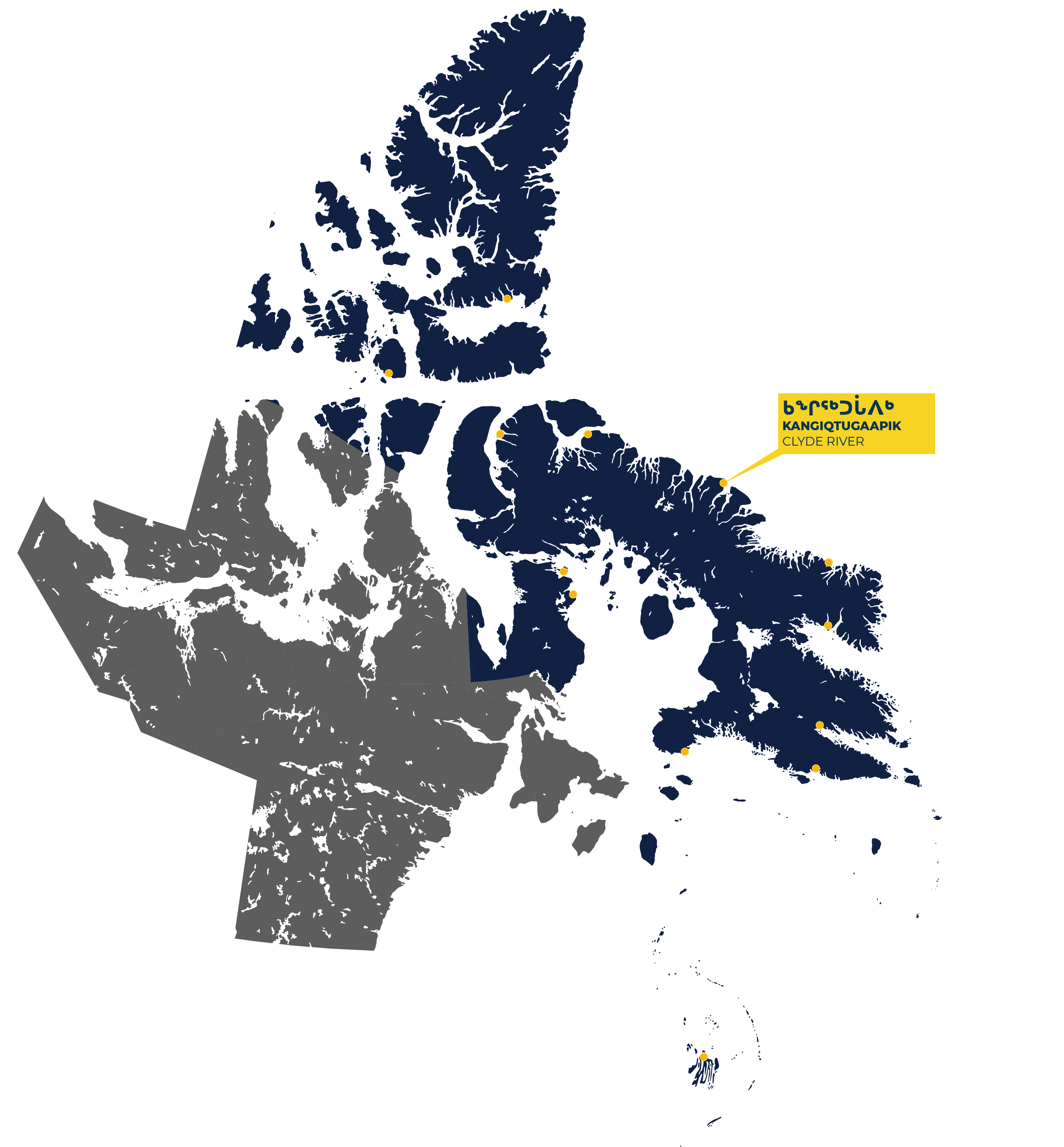

Clyde River / Kangiqtugaapik

1,183 Total Population

96.8% Inuit Population

95.9% Inuktitut Speaking

25.6 Average Age

15.4% Population with Highschool Diploma

The hamlet of Clyde River is located on the east coast of Baffin Island on the western shore of Patricia Bay. The nearby fiords stretch towards the oldest ice cap in Canada, the Barnes Ice Cap, and are known for having some of the most spectacular scenery in Canada.

Clyde River is also known locally as Kangiqtugaapik. The words mean “a nice little inlet.” Inuit of Clyde River call themselves Kangiqtugaapimuit. They are well known for their commitment to maintaining Inuit knowledge and for their artwork, especially soapstone carvings and silkscreens.

Over the years, Kangiqtugaapimiut have continued to work to combine their traditional way of life with community life. The Ilisaqsivik Society is dedicated to promoting Inuit culture and language and was instrumental in pursuing the Piqqusilirivvik Inuit Cultural Learning Facility, a cultural school established in Clyde River in 2011. This school provides opportunities to young Inuit to immerse themselves in traditional harvesting, sewing and Inuit cultural activities.

History

For generations, Inuit families have migrated through the area which is abundant with narwhal, seal, polar bears and other local resources. With the establishment of the Hudson’s Bay Company trading post in 1924, families from Kimmirut, Kinngait, Iqaluit and Pangnirtung were relocated to the settlement.

As government programs arrived in the 1960s, the population of Clyde River doubled as Inuit were coerced off the land and into the settlement. Along with this came a tuberculosis epidemic and separation of families as children were forced to attend residential schools.

In 1970, the decision was made to move the community from the east side to the west side of Patricia Bay to take advantage of better ground conditions for building.

In March 2019, the Government of Canada issued a formal apology to Inuit for its actions on the Tuberculosis epidemic from the 1940s to 1960s. In August 2019, the Government of Canada formally acknowledged and apologized for its colonial actions and policies towards Inuit in the Qikiqtani Region between 1950 to 1975.

To learn more about the history of Inuit and the community of Clyde River, visit the Qikiqtani Truth Commission Community History.

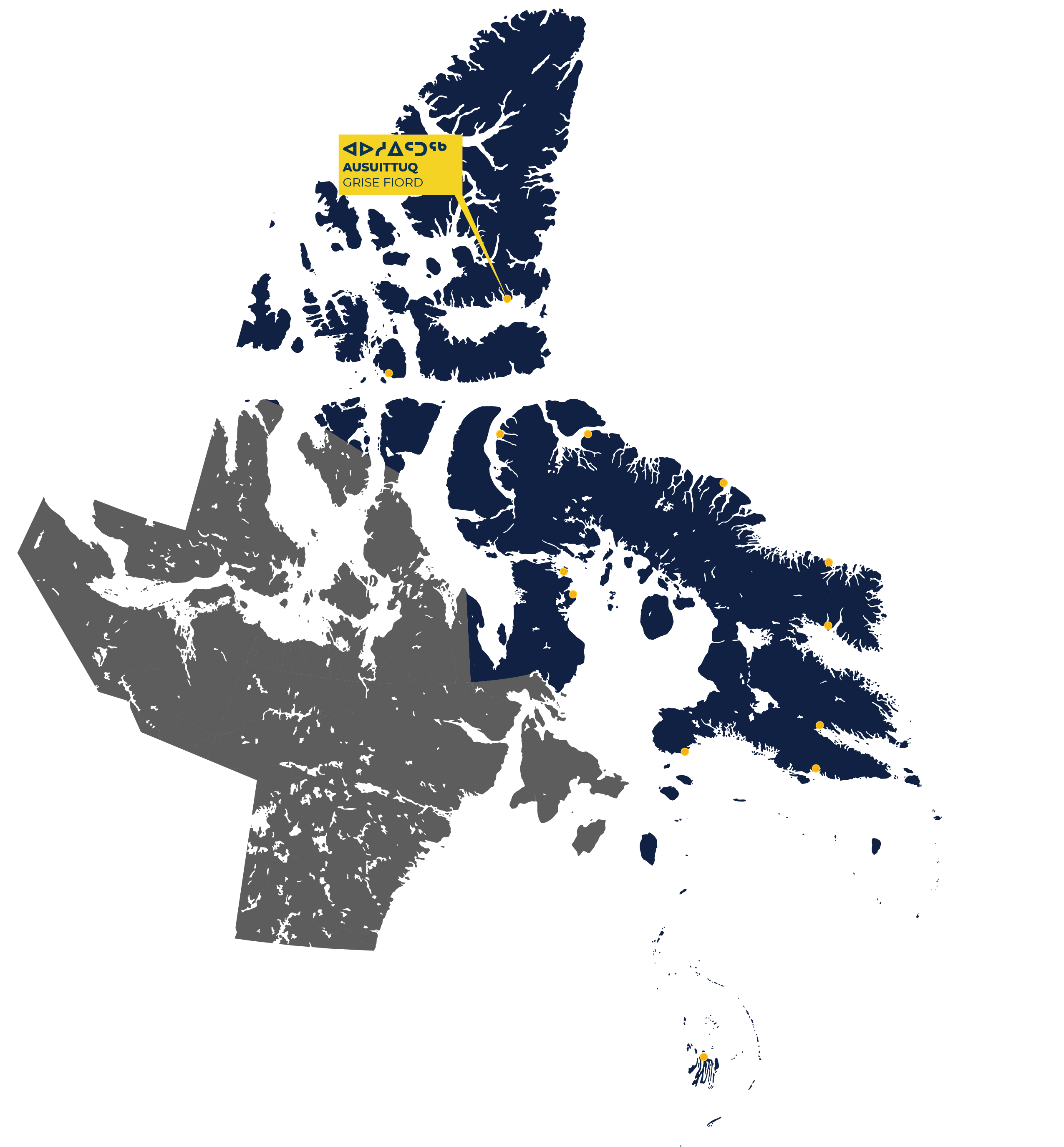

Grise Fiord / Ausuittuq

144Total Population

93% Inuit Population

77.5% Inuktitut Speaking

30.9 Average Age

15% Population with Highschool Diploma

Grise Fiord, located on the southern shore of Ellesmere Island, is the northernmost community in North America. The Inuktitut name for the community is Ausuittuq, meaning “the place that never thaws.”

The name Grise was given to the fiord by Norwegian explorer Otto Sverdrup during his exploration expedition from 1898 to 1902. The name means “pig inlet” in Norwegian, referencing the appearance of the walruses that Sverdrup saw in the fiord.

Grise Fiord is known for its striking terrain and environment. The sea is frozen for ten months of the year, with break-up occurring in mid-August. From May to August, the sun never sets, and from October to mid-February, it never rises. Grise Fiord is considered one of the coldest communities in the world, with an average yearly temperature of -16 °C.

Today, after calling the community home for half a century, Inuit from Grise Fiord call themselves Ausuittumiut. Harvesting is an important part of life in Grise Fiord and community members harvest seal, walrus, narwhal, beluga whale, polar bears and muskox.

History

In 1922, a small enclave of year-round residents was created with the establishment of a small RCMP detachment at Craig Harbour, approximately 55 km east of Grise Fiord. The primary role of the post was to demonstrate Canadian sovereignty over Canada’s Arctic Archipelago.

As part of government-sponsored relocation programs of the 1950s, a permanent Inuit settlement was planned for Ellesmere Island. In 1953 and 1955, families from Pond Inlet who called themselves Mittimatalingmiut or Tununirmiut, and families from Inukjuak, Quebec, known as Itivimiut, were moved to the area through forced relocation. In effect, Inuit were used as human flag poles to achieve Canada’s nation-building agenda in the Arctic. In the process families were separated, communities fragmented, and cultural traditions lost. Along with this relocation also came a tuberculosis epidemic and separation of families as children were forced to attend residential schools.

The settlement was originally located on the Lindstrom Peninsula, 70 km west of the RCMP detachment, and 8 km west of Grise Fiord. In 1956, the RCMP relocated their post to Grise Fiord, and the Inuit settlement moved in 1961 when the school was opened. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, some residents, especially families from Inukjuak, left Grise Fiord to return to their previous homes. Others moved to the community from Pond Inlet and Inukjuak to be closer to family and friends.

In March 2019, the Government of Canada issued a formal apology to Inuit for its actions on the Tuberculosis epidemic from the 1940s to 1960s. In August 2019, the Government of Canada formally acknowledged and apologized for its colonial actions and policies towards Inuit in the Qikiqtani Region between 1950 to 1975.

To learn more about the history of Inuit and the community of Grise Fiord, visit the Qikiqtani Truth Commission Community History.

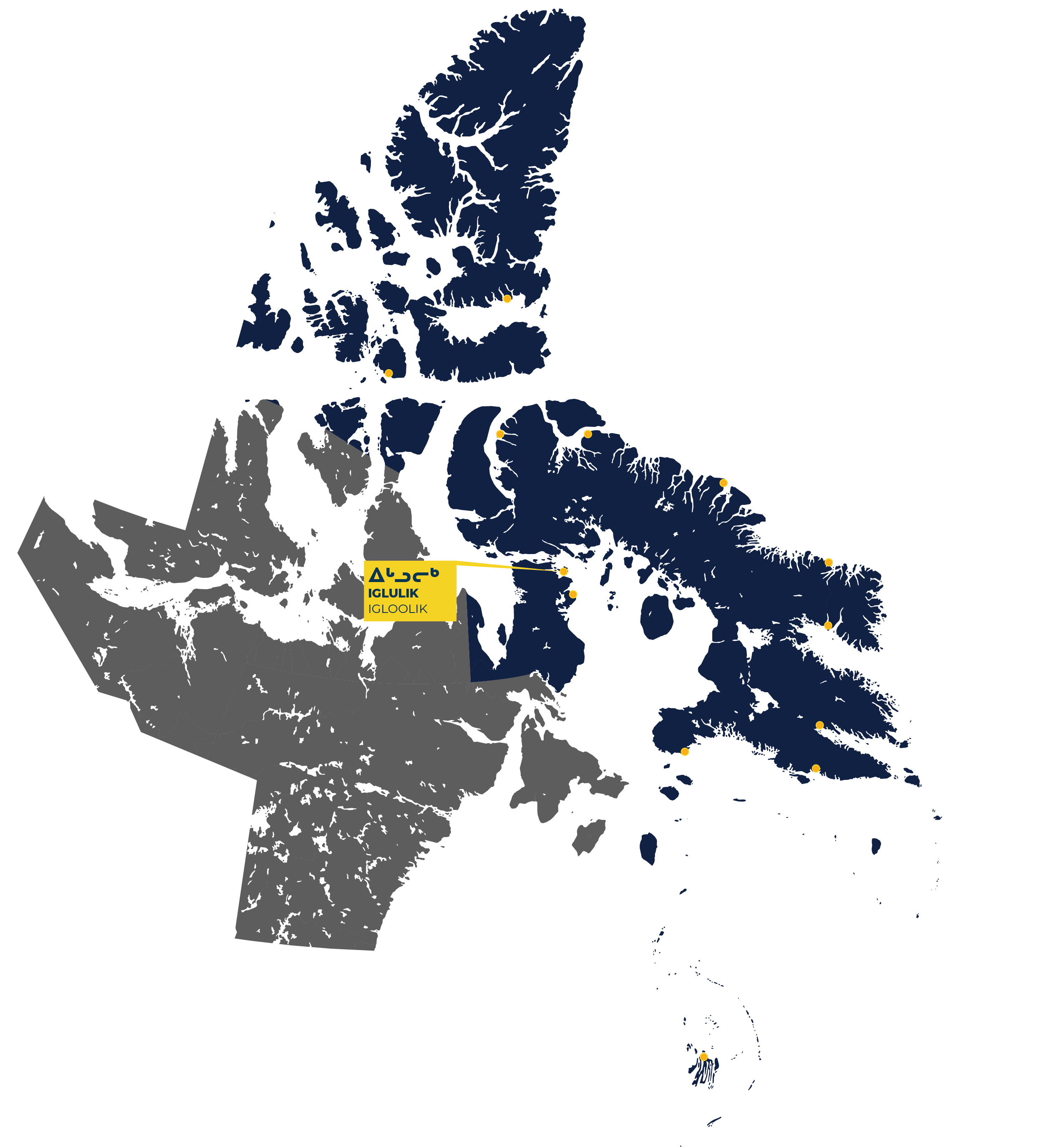

Igloolik / Iglulik

2,049 Total Population

94% Inuit Population

90% Inuktitut Speaking

24.5 Average Age

13% Population with Highschool Diploma

Igloolik, meaning “there is a house there” is located on Foxe Basin, about 70 km north of Sanirajak. Before services and people were concentrated at the present hamlet, Igloolik, meaning, “there is a house there,” was the name given to a cluster of large pre-contact dwellings east of the present community. The name was later applied to Igloolik Point and Igloolik Island. The bay in front of the present hamlet was called Turton Bay by nineteen-century explorers.

Igloolik, is the second-largest community in the Qikiqtani Region, but it was among the last to be firmly called home by its local population. Inuit in the area lived in seasonal ilagiit nunagivaktangit, a place regularly used for hunting, harvesting and gathering. Inuit traditionally had several ilagiit nunagivaktangit, which allowed them to move to follow. Unlike many other communities across the Arctic, many of Igloolik’s families occupied ilagiit nunagivaktangit until well into the 1960s.

Sea ice is highly important to the region’s settlement and history. New ice forms in Foxe Basin during the month of October, and by November Foxe Basin is completely covered. The ice starts melting in May or June, but it is not until August that it begins to rapidly break up.

Igloolik is a community with strong Inuit traditions. It has been called the cultural epicentre for the Inuit people. The marine environment around Igloolik has long supported a large population. The cultural richness of the community is known outside Nunavut through many efforts, including a long-lasting oral history project, dedicated ethnologists and other social scientists, and Igloolik artists.

Today, Igloolik is a thriving community that is home to two video production organizations: Igloolik Isuma Productions Inc. and a local office of the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation. The award-winning Canadian film Atanarjua: The Fast Runner was filmed in Igloolik.

History

Information about the area’s earliest Inuit inhabitants comes from many archaeological sites on Igloolik island, some of which date back more that 4,000 years.

The first documented visit by Europeans to Foxe Basin was in 1822-23, when two English Royal Navy vessels sailed into the basin. Later, in 1867 and again in 1868, American explorer Charles Hall traveled to the area to investigate the fate of the missing Franklin Expedition.

The first permanent presence in Igloolik came with the establishment of the Roman Catholic Mission in the 1930s. By the end of the decade, the Hudson’s Bay Company had also set up a post on the island.

In 1955, when the Cold War resulted in the establishment of a chain of Distant Early Warning (DEW) radar sites, the southern part of the region’s annual routines were transformed when a site was established 70 km south of Igloolik, at Sanirajak. The DEW site provided new opportunities for casual employment, medical care, and other attractions.

In the mid-1950s, major change came to the Igloolik region. The government of Canada’s policy was to encourage Inuit to adopt southern ways. Over the next several years, children were separated from their parents because of treatment of tuberculosis and forced residential schooling. Dog teams were eliminated by local authorities with excuses such as illness and disease.

In March 2019, the Government of Canada issued a formal apology to Inuit for its actions on the Tuberculosis epidemic from the 1940s to 1960s. In August 2019, the Government of Canada formally acknowledged and apologized for its colonial actions and policies towards Inuit in the Qikiqtani Region between 1950 to 1975.

To learn more about the history of Inuit and the community of Igloolik, visit the Qikiqtani Truth Commission Community History.

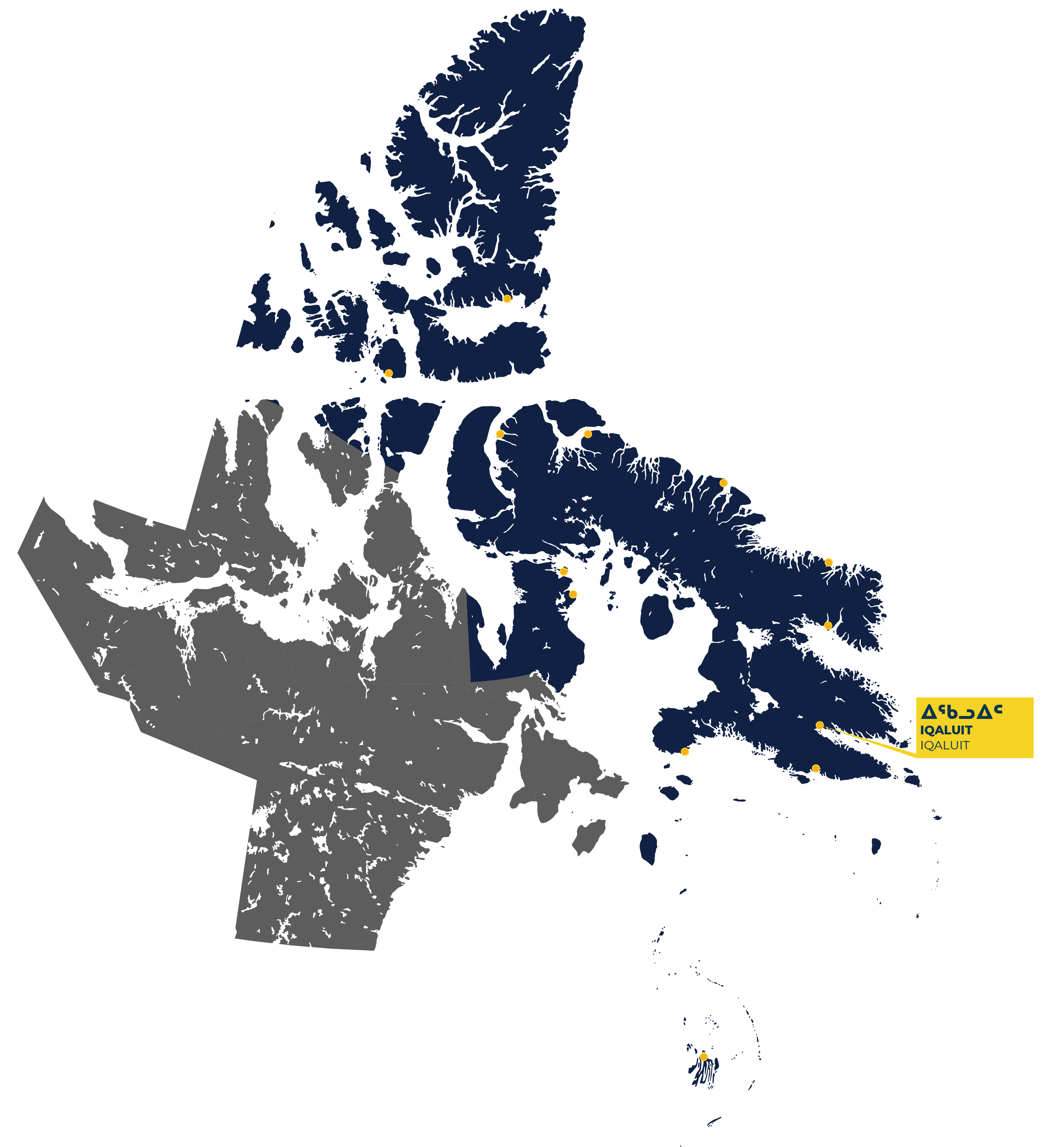

Iqaluit

7,429 Total Population

58.5% Inuit Population

42% Inuktitut Speaking

31 Average Age

19% Population with Highschool Diploma

The city of Iqaluit is a community unlike any other in Nunavut. Previously known as Frobisher Bay, Iqaluit is Nunavut’s biggest community, it’s only city and is the capital of the Canadian Territory. In Inuktitut, Iqaluit means “place of many fish”, referring historically to the prosperous fishing grounds in the area.

Iqaluit is at the head of a large tidal basin, Frobisher Bay, or ‘Tasiujarjuaq’ in Inuktitut, and is situated on the shores of Koojesse Inlet. Dramatic tides create long stretches of rocky beaches and mud flats along the inlet. Freeze-up of Frobisher Bay generally occurs in November and lasts until June.

Iqaluit is home to the main territory government offices. Nunavut’s main hospital is in Iqaluit as well as the Nunavut Arctic College. Residential subdivisions have spread to the areas surrounding Iqaluit.

Iqaluit has a steady flow, and much turnover, of incomers attached to government work or business. As the major medical centre and air-travel hub of the Eastern Arctic, Iqaluit gives temporary shelter to travellers from all over Nunavut.

History

Historically, Iqaluit, and the surrounding area, was known mainly as a good place to fish in the summer, and as a place where the coast-dwelling Inuit of Frobisher Bay passed enroute to caribou-hunting grounds in the centre of Baffin Island.

Non-Inuit institutions arrived late to the Frobisher Bay area compared with other places in the Qikiqtani Region. In 1914 the Hudson’s Bay Company established a post at Charles Francis Hall Bay. In 1920, it moved across to Hamlin Bay, and shifted again two years later to Ward Inlet, east of Iqaluit. Inuit called the Ward Inlet post Iqalugaarjuit. In 1948, the HBC finally established a more permanent post at Niaqunnguut, which is the present-day Iqaluit neighbourhood of Apex.

It was the development of a landing strip for the American military and the intrusion of modern geopolitics and defence into Inuit Nunangat, rather than social services or trade opportunities, that concentrated Inuit towards the head of Frobisher bay in the 1940s. Iqaluit attracted hunters and their families from around Frobisher Bay and also Hudson Strait and Cumberland Sound.

Because of the strong development pressures from military and central administrative activities, Iqaluit followed a unique path through the 1950s and 1960s. Most other Qikiqtani communities began as isolated trading posts, lived through an intensive period of disruption, and settled down in a few years as home to those who had formerly hunted and trapped in the surrounding area. Iqaluit was different. The surrounding population was small. Steady increases from migration within the Qikiqtani Region, as well as the arrival of non-Inuit from all over Canada, was due, in large part, to the airfield.

The steady pace of growth made Iqaluit both the largest mixed community and the largest non-Inuit community in Nunavut.

In the mid-1950s the United States built the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line across the Arctic. The Canadian government formed the subdivision of Apex Hill (present day Apex), where the HBC post was located, in 1955.

By 1960, there were no longer any permanent outlying Inuit camps left in the Frobisher Bay region.

In spite of its investment in Apex and the airport, Canadian officials expressed concerns that Iqaluit’s future was uncertain. As a result, investment in infrastructure and services was done using a “temporary-only” approach. The challenges of accommodating Inuit in places created for the military were evident in the condition of community infrastructure. Wastewater was too close to drinking water. Housing was over-crowded and poorly build.

In 1963 the last of the US Air Force personnel left Iqaluit and the community was fully in the hands of the Canadian Government. In 1966, the federal government determined the settlement of Iqaluit would retain its role as a regional hub, and began investing in permanent housing, schools and other infrastructure.

In 1999, Iqaluit became the capital of Nunavut after the division of the Northwest Territories into two separate territories.

In March 2019, the Government of Canada issued a formal apology to Inuit for its actions on the Tuberculosis epidemic from the 1940s to 1960s. In August 2019, the Government of Canada formally acknowledged and apologized for its colonial actions and policies towards Inuit in the Qikiqtani Region between 1950 to 1975.

To learn more about the history of Inuit and the community of Iqaluit, visit the Qikiqtani Truth Commission Community History.

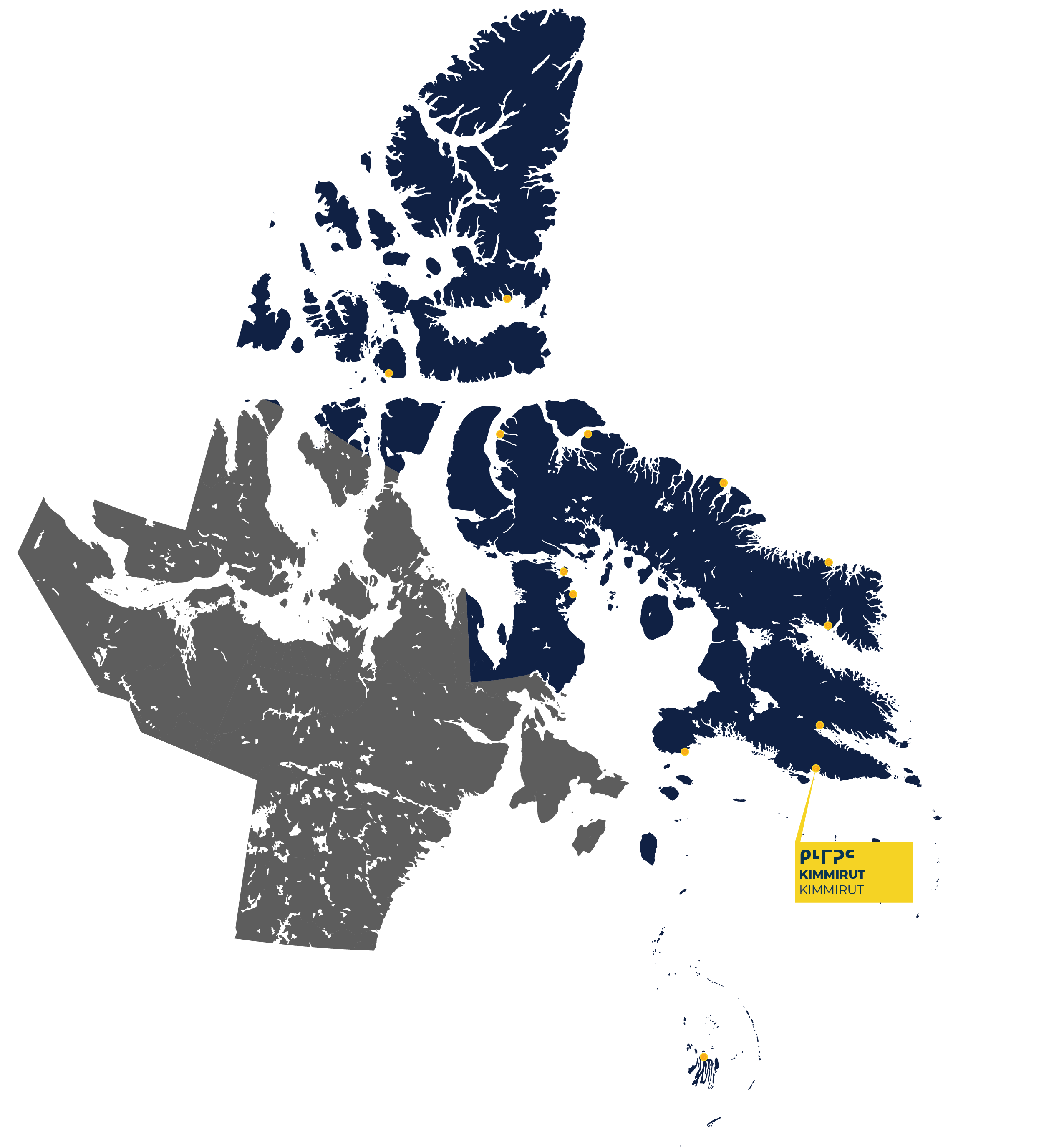

Kimmirut

426 Total Population

92.5% Inuit Population

90% Inuktitut Speaking

28.3 Average Age

23.5% Population with Highschool Diploma

The southernmost community on Baffin Island, Kimmirut is located at the northeast end of Glasgow Inlet. Originally known as Lake Harbour, in 1996 the hamlet changed its name to Kimmirut, which means heel in Inuktitut. It was named for the distinctive rocky outcrop in the inlet where it is located, which looks like the back of a foot.

The bays and inlets around Kimmirut create dramatic tidal occurrences, such as reversible falls, tidal bores and boiling rip tides. Kimmirut is sheltered by rocky hills and mountains however it experiences extreme shifts in weather and temperatures throughout all seasons.

For many Kimmirummiut, artwork has become an important source of income and cultural life. Three types of soapstone are found in the region, as well as marble and semi-precious stone. Many carvers from Kimmirut are well known worldwide.

Surrounded by stunning scenery, Kimmirut is situated at the mouth of the Soper River and is a short distance from Katannilik Territorial Park.

History

Inuit have inhabited the region along the central southern coast of Baffin Island for thousands of years. Kimmirummiut were among the first Inuit in Qikiqtani Region to have extensive contact with non-Inuit. The Anglican Church, the Hudson’s Bay Company and the RCMP arrived in Kimmirut during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Inuit in the area lived in seasonal ilagiit nunagivaktangit, a place regularly used for hunting, harvesting and gathering. Inuit traditionally had several ilagiit nunagivaktangit, which allowed them to move to follow game. By the 1950s, the majority of Inuit in the area still lived in ilagiit nunagivaktangit, but many families made regular visits to Lake Harbour for trade, medical care, or seasonal employment opportunities.

During the 1950s, the population of the Kimmirut area began to decline. Some people left to find employment in Iqaluit, which was growing quickly in response to the combination of military and government activities. Other people left the area because they or their family members were sent south for medical treatment. The number of ilagiit nunagivaktangat declined as remaining families preferred to live closer together.

The loss of nearly 80 per cent of the area’s qimmiit (sled dogs) during a rabies outbreak in 1960 was a tragic event in Kimmirut. Although the dog population improved through careful management and sharing of teams by families, the loss was compounded by more rigorous enforcement of strict control measures by authorities in the settlement in the following years.

Afraid that the Hudson’s Bay Company post at Kimmirut would close due to the combination of fewer hunters and lower fur prices, the government took limited action during the 1960s to provide a school, more medical services and Southern-style housing for Inuit moving into the settlement. It was during this period that dramatic social, economic, and political changes affected everyone in the region. By 1969, only one ilagiit nunagivaktangat remained in the area.

In March 2019, the Government of Canada issued a formal apology to Inuit for its actions on the Tuberculosis epidemic from the 1940s to 1960s. In August 2019, the Government of Canada formally acknowledged and apologized for its colonial actions and policies towards Inuit in the Qikiqtani Region between 1950 to 1975.

To learn more about the history of Inuit and the community of Kimmirut, visit the Qikiqtani Truth Commission Community History.

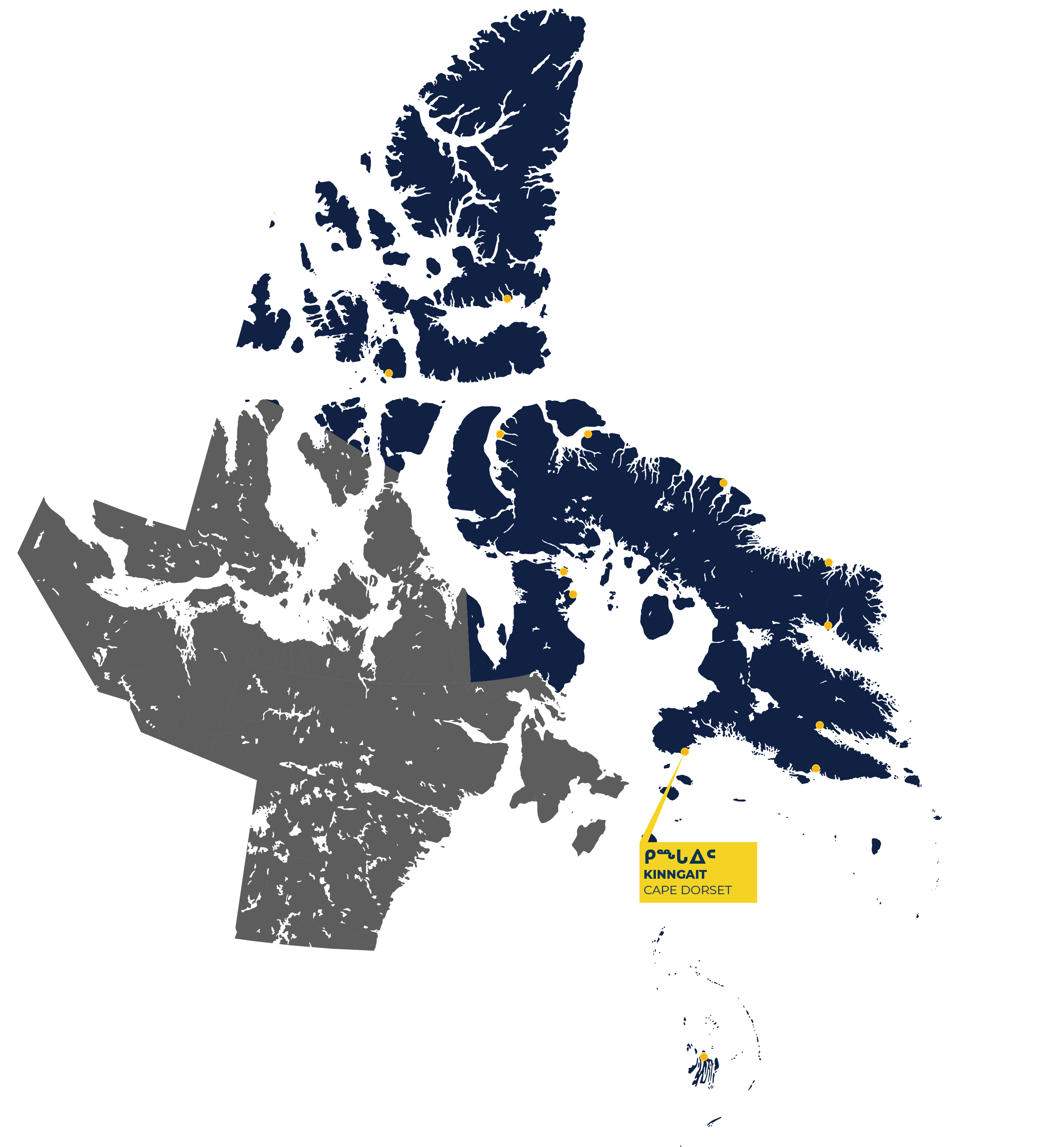

Kinngait

1,396 Total Population

93% Inuit Population

92% Inuktitut Speaking

26.6 Average Age

14% Population with a high school diploma

Kinngait (temporarily known as Cape Dorset), is located on the north side of Dorset Island, near Foxe Peninsula, at the southern tip of Baffin Island. Foxe Peninsula is characterized by high, rugged hills, known as the Kinngait Range, which reaches their highest elevation on Dorset Island.

Inuit named the area Kinngait, which describes the high, undulating hills surrounding the communities protected harbour. Locally, the community is also referred to as Sikusilaq, after a local inlet that remains ice-free throughout the year. In 1631, Kinngait was named by a British Captain after the Fourth Earl of Dorset.

Kinngait is recognized as the “Capital of Inuit Art” and since the 1950s has been a centre for drawing, printmaking and carving. QIA is a proud sponsor of the Kenojuak Cultural Centre and Print Shop which opened in 2018. The Centre serves as an art studio and exhibition space for local artists, as well as a community centre.

Today, Kinngait is known as one of the most important cultural centres in Canada, for its art production and Thule culture archaeological sites.

History

Kinngait is known to have been inhabited for at least two thousand years, originally by Tuniit or Dorset people, and then by Inuit. The region was home to many multi-family groups whose harvesting patterns were guided by wild game and environmental conditions.

In 1913 the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) established a trading post on Dorset Island. Initially, only a few Inuit families came to Kinngait to live year-round and work for the trading post. In the 1930s, the HBC received permission from the federal administration to relocate people from Kinngait to new trading posts further north. This venture failed and most Inuit were relocated to Arctic Bay, as well as other current communities in Nunavut.

During the 1950s the Canadian Government coerced many Kinngaimmuit to abandon camp life and establish themselves in the community. This movement towards centralization was caused in large part by the consolidation of government services in Kinngait.

Centralization led to a culling of qimmiit (sled dog) population by local authorities.

In March 2019, the Government of Canada issued a formal apology to Inuit for its actions on the Tuberculosis epidemic from the 1940s to 1960s. In August 2019, the Government of Canada formally acknowledged and apologized for its colonial actions and policies towards Inuit in the Qikiqtani Region between 1950 to 1975.

To learn more about the history of Inuit and the community of Kinngait, visit the Qikiqtani Truth Commission Community History.

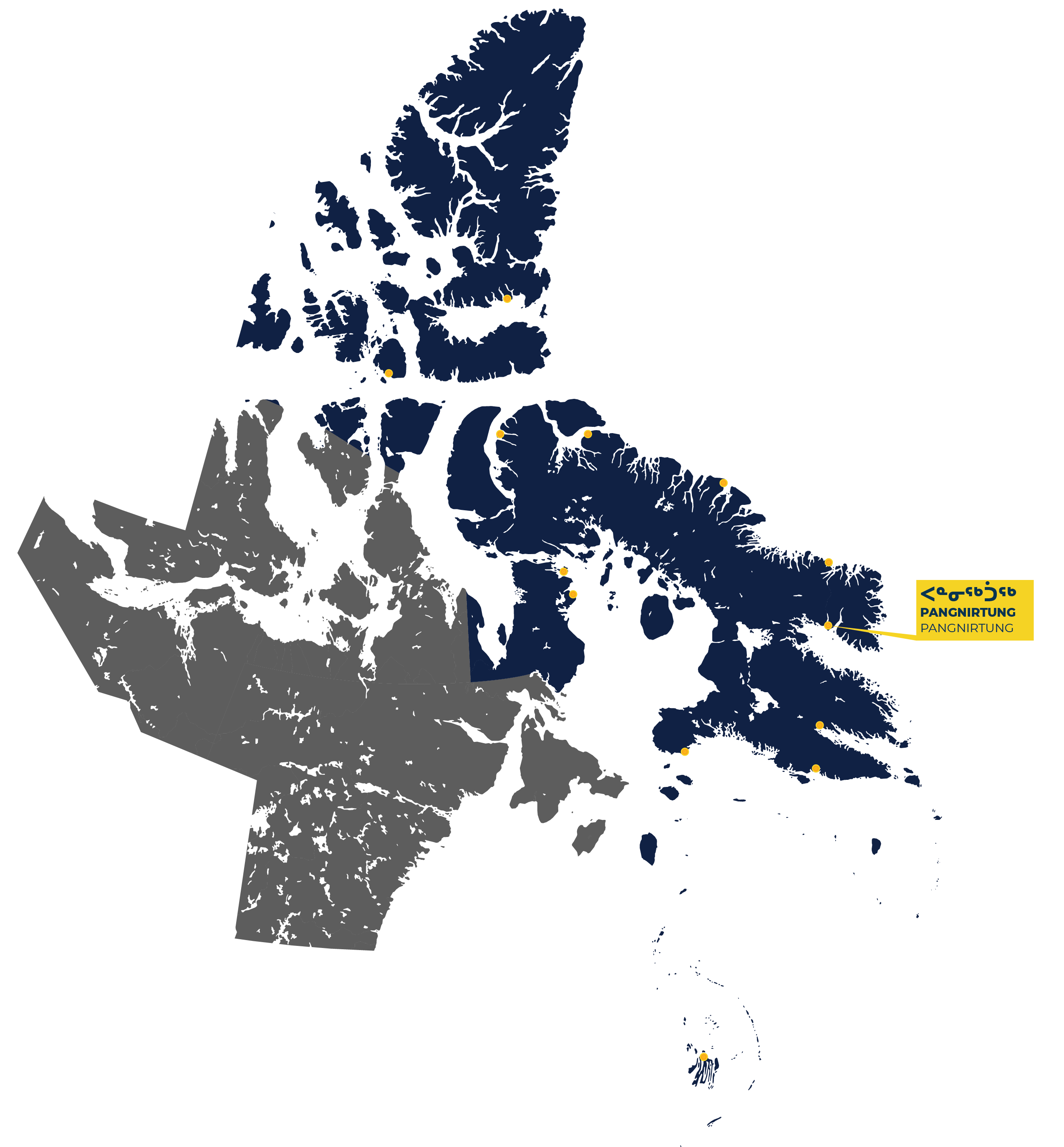

Pangnirtung / Panniqtuuq

1,504 Total Population

93.8% Inuit Population

90.8% Inuktitut Speaking

27.9 Average Age

13% Population with Highschool Diploma

Pangnirtung is the third-largest community in the Qikiqtani Region. Pangniqtuuq, meaning ‘place of bull caribou’ in Inuktitut, is situated at the mouth of Pangnirtung Fjord beneath scenic mountains. Pangnirtung Fjord eventually merges with Cumberland Sound. The waters surrounding Pangnirtung provide a particularly rich habitat for marine mammals. Pangnirtung is the southern gateway to Auyuittuq National Park and the vertical cliff of Mount Thor.

Pangnirtung community members have a long history of producing traditional arts including prints, sculptures, and carvings made from local stone. In 1970, weaving was introduced to the women of Pangnirtung as a livelihood opportunity. Since then, tapestry weaving has flourished. In 1991, the Uqqurmiut Centre for Arts and Crafts was built which includes a tapestry studio, print shop, and craft gallery.

Today, Pangnirtung has continues to have a strong arts industry. The Uqqurmiut Centre offers a place for local artists to work and display their lithographs prints, sculptures and famous tapestries. Pangnirtung also has a thriving fishing industry and operates one of the few inshore commercial fisheries in Nunavut.

History

Pangnirtung has only seen permanent habitation since 1921. It grew around the Hudson’s Bay Company trading post that attracted the RCMP in 1923, an Anglican Mission in 1926, and a government hospital in 1930.

The history of Cumberland Sound is unique in the Qikiqtani Region. Its people lived through three waves of change since 1824. The first was the whaling era, from 1824 to 1919. Many whalers established permanent stations in Cumberland Sound. During this time many cultural changes were experienced, as well as population losses due to disease, and the near extinction of the bowhead whale.

The second wave of change began in 1921, when the population, which was once densely located around the islands and shorelines ringing Cumberland Sound, scattered into ilagiit nunagivaktangit places regularly used for hunting, harvesting and gathering. Inuit traditionally had several ilagiit nunagivaktangit, which allowed them to move to follow game. Inuit followed and harvested game and traveled to Pangnirtung to trade for imported foods and goods. This remained the annual routine until 1962, when a growing number of government officials and services at Pangnirtung drove a third wave of change. Housing, health care, employment opportunities and forced residential schooling coerced Inuit to the settlement and by 1970, most Inuit had been relocated permanently to Pangnirtung.

In March 2019, the Government of Canada issued a formal apology to Inuit for its actions on the Tuberculosis epidemic from the 1940s to 1960s. In August 2019, the Government of Canada formally acknowledged and apologized for its colonial actions and policies towards Inuit in the Qikiqtani Region between 1950 to 1975.

To learn more about the history of Inuit and the community of Pangnirtung, visit the Qikiqtani Truth Commission Community History.

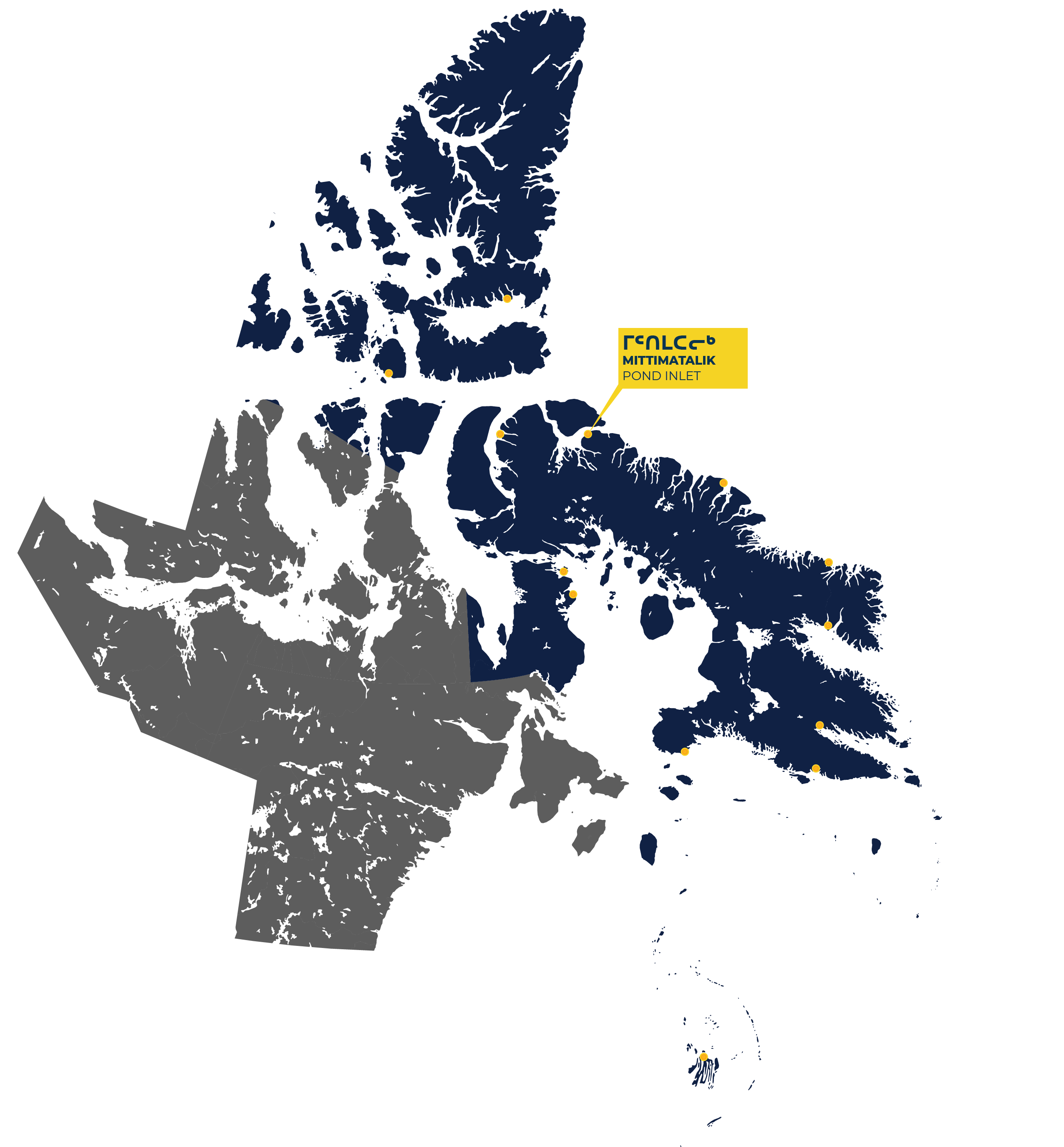

Pond Inlet / Mittimatalik

1,555 Total Population

93% Inuit Population

92% Inuktitut Speaking

26 Average Age

16% Population with Highschool Diploma

Pond Inlet, Mittimatalik, is located on the east side of Eclipse Sound, about 700 km north of the Arctic Circle on Baffin Island. Its local Inuktitut name is Mittimatalik, and the people of the region are known as Tununirmiut, which is thought to mean “people of the shaded place” or Mittimatalingmiut, meaning “people of Mittimatalik.” The hamlet shares its name with an arm of the sea that separates Bylot Island from Baffin Island. The name “Pond’s Bay” was chosen by an explorer in 1818 in honour of an English astronomer.

Pond Inlet is considered one of Canada’s Jewels of the North. It is extremely picturesque with mountain ranges viewable from all directions and is one of the access communities to Sirmilik National Park.

Pond Inlet is a thriving community that gained recognition in 2019 for the preschool Pirurvik. Pirurvik: A Place to Grow is an early childhood education centre that was awarded the Arctic Inspiration Prize. The QIA supported program, which began in 2016, is based on the Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (Inuit traditional knowledge) principle pilimmaksarniq, which allows children to learn at their own pace.

History

The region has been occupied for four thousand years, through the pre-Dorset, Dorset, Thule, and modern Inuit periods. Since the earliest times, people hunted on land, sea, and ice. Ringed seals, whales, and other marine mammals were the most important part of the diet. Evidence of a rich culture is evidenced by cultural objects preserved in the ground, most famously two shaman’s masks carved more than one thousand years ago, which were found at Button Point.

A settlement grew along the shoreline of Eclipse Sound. Trading establishments started here in 1903 when Scottish entrepreneurs set up a small whaling station. Over the next twenty years, Qallunaat (non-Inuit) managers opened several small stations scattered around the region.

The Hudson’s Bay Company settled at the present Pond Inlet in 1921. The RCMP post arrived in 1922 and two missions (Roman Catholic and Anglican) came in 1929. Between 1945 and 1962 Government interest in Pond Inlet intensified and schools opened. Along with this came a tuberculosis epidemic and separation of families as children were forced to attend residential schools.

Between 1962 to 1964 a tote road to the Mary River mine was opened. Amongst the richest iron ore deposits ever discovered, the Mary River mine is still in operation today. It is located about 150km from Pond Inlet.

Between 1964 and 1975 Inuit experienced a rapid disconnect to the land, culture and way of life as increased pressure by the federal government was put on Inuit families to centralize in Pond Inlet. During those years, children were separated from their parents because of treatment of tuberculosis and forced residential schooling.

In March 2019, the Government of Canada issued a formal apology to Inuit for its actions on the Tuberculosis epidemic from the 1940s to 1960s. In August 2019, the Government of Canada formally acknowledged and apologized for its colonial actions and policies towards Inuit in the Qikiqtani Region between 1950 to 1975.

To learn more about the history of Inuit and the community of Pond Inlet, visit the Qikiqtani Truth Commission Community History.

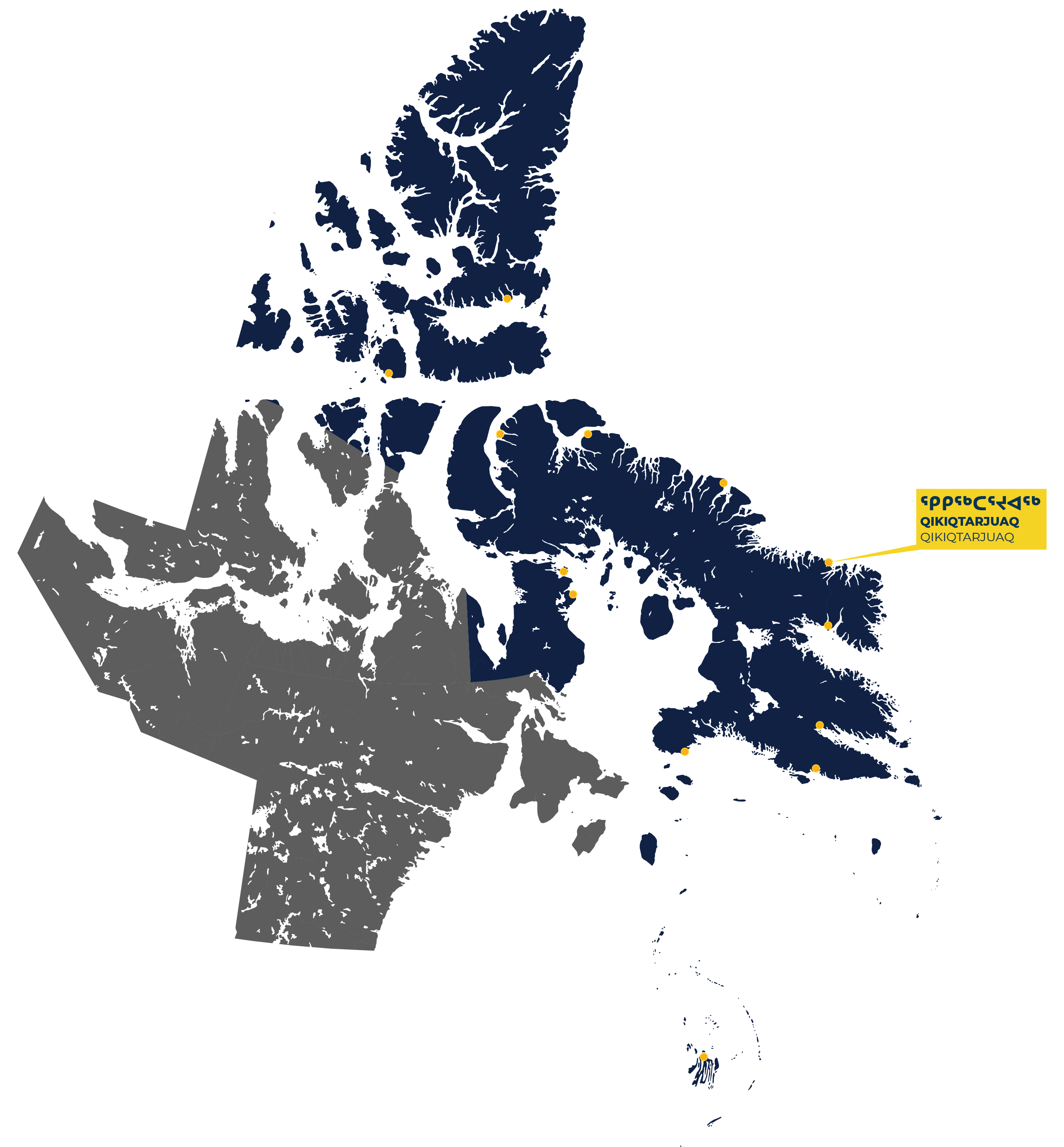

Qikiqtarjuaq / Qikiqtaqjuak

593 Total Population

94% Inuit Population

93.6% Inuktitut Speaking

27.9 Average Age

9.8% Population with Highschool Diploma

The hamlet of Qikiqtarjuaq is located on Broughton Island, 2.5 km off the east coast of Cumberland Peninsula on Baffin Island. The community was formerly known as Broughton Island. To reclaim Inuit history and language Inuit renamed their community Qikiqtarjuaq or “big island” in 1998.

Qikiqtarjuaq has some of the most dramatic terrain in Canada. Mountains of many shapes tower above fiords with sides that plunge into the sea, and icebergs are abundant. Some claim Qikiqtarjuaq is the iceberg capital of the world. Qikiqtarjuaq is the northern gateway to Auyuiituq National Park and the world-famous Mount Thor.

History

For generations, Inuit in Qikiqtarjuaq lived with their kin in a number of ilagiit nunagivaktangi that were carefully located, moved and organized to take advantage of wildlife conditions. Ilagiit nunagivaktangit were places regularly used for hunting, harvesting and gathering. Inuit traditionally had several ilagiit nunagivaktangit, which allowed them to move to follow game. Frequented camp locations included Kivitoo, to the north of Broughton Island, and Paallavvik, or Padloping Island, to the south. In a lightly populated area, with a mobile population, these places were important locations for harvesting, gathering, and meeting other families.

The daily and seasonal routines of Qikiqtarjuarmiut changed dramatically and almost instantly in 1955 when Broughton Island was chosen as the site for an auxiliary Distant Early Warning Line station. The DEW Line sites, especially at Qikiqtarjuaq, provided opportunities for both steady and ad hoc jobs for Inuit. As a result, many Inuit arrived to look for possibilities of employment or to gather leftover building materials and surplus food.

The construction of the DEW Line resulted in a rapid increase in settled population over a short period. Fifteen Inuit were continuously, though briefly, employed during construction, and most probably brought their immediate families and relatives with them. In 1962, both the school and the HBC store were relocated closer to the DEW Line station.

The influx of Qallunaat (non-Inuit) into the region led to an increase in infectious diseases against which the Inuit had no immunization. Polio was reported in 1959, whooping cough was recorded in 1960 and Tuberculosis caused the evacuation of several persons each year.

In the early 1960s the Government instituted actions to discourage Inuit from living in their traditional camps at Kivitoo, Paallavvik, and other nearby isolated places. Enticements to move included promises of housing and health care. Many Qikiqtarjuarmiut have since admitted that they felt coerced into relocating. They were told that if they stayed on the land they would not receive emergency medical care, that their children would suffer without a proper education, or that their food rations would not be delivered.

By 1968, the Kivitoo and Padloping settlements were completely abandoned and their residents were relocated to Qikiqtarjuaq.

In March 2019, the Government of Canada issued a formal apology to Inuit for its actions on the Tuberculosis epidemic from the 1940s to 1960s. In August 2019, the Government of Canada formally acknowledged and apologized for its colonial actions and policies towards Inuit in the Qikiqtani Region between 1950 to 1975.

To learn more about the history of Inuit and the community of Qikiqtarjuaq, visit the Qikiqtani Truth Commission Community History.

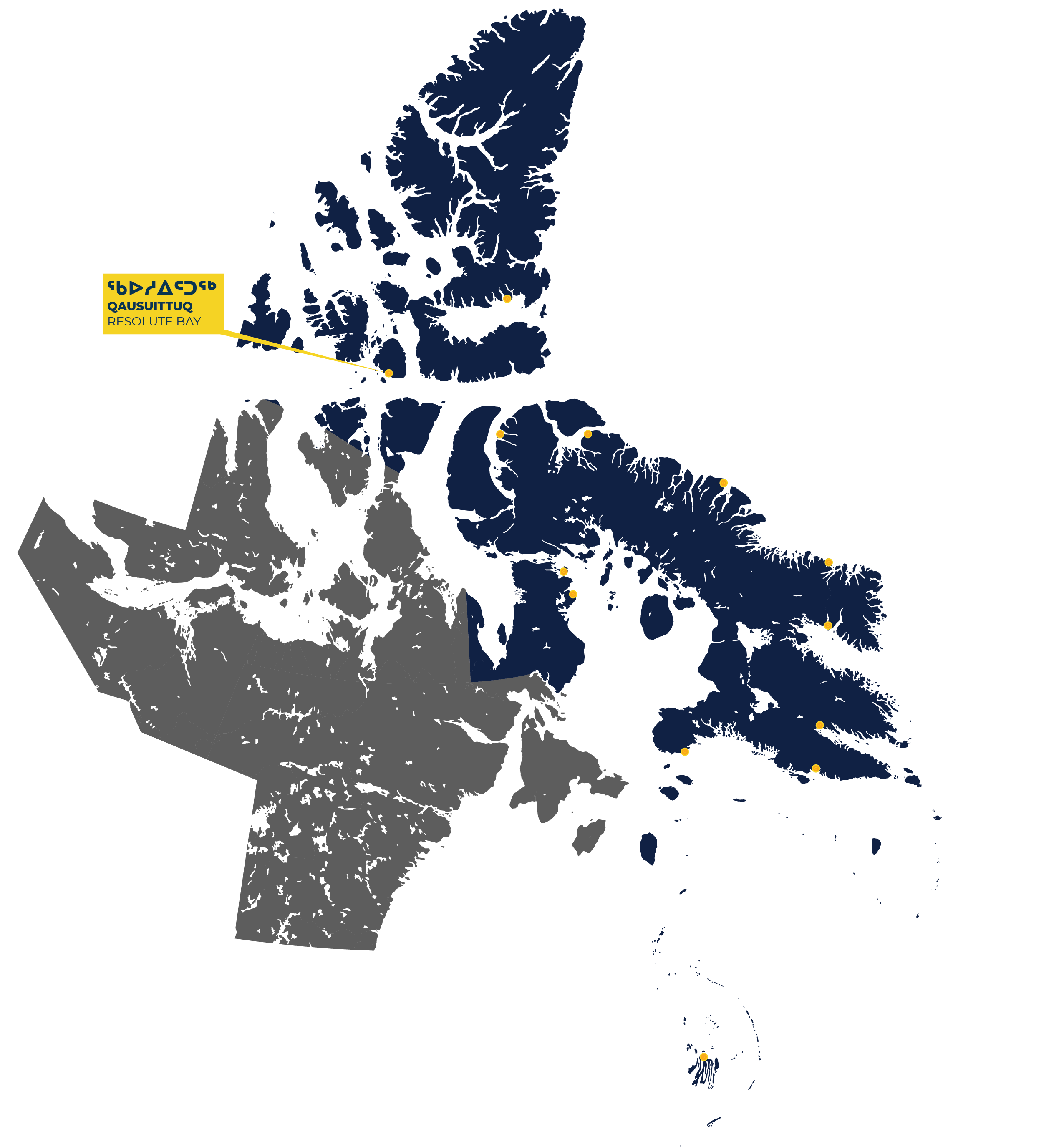

Resolute Bay / Qausuittuq

183 Total Population

83% Inuit Population

65.6% Inuktitut Speaking

27.8 Average Age

11.5% Population with Highschool Diploma

Resolute Bay, Qausuittuq, is located on the Bay it is named after on the south shore of Cornwallis Island, one of the Queen Elizabeth Islands. It was named after the ship HMS Resolute, which participated in the search for Sir John Franklin’s expedition in the 1850s. The Inuktitut names for the community are Qausuittuq, meaning “the place with no dawn,” and Qarnartakuj, meaning “the place of the ruins,” which refers to the piles of whalebones marking a centuries-old Thule settlement site near the hamlet. The people of Resolute Bay call themselves Qausuitturmiut.

The land is compromised of low-lying plains and plateaus that create an almost featureless terrain scattered with rock debris. Cornwallis Island has many small lakes and numerous inlets and bays mark its coastline. The marine area between the islands of the High Arctic provides important migratory routes for marine mammals.

Today, Resolute Bay is an important centre for exploration and scientific research in Canada’s Arctic. The community has a weather station and is home to a Polar Continental Shelf Project research base that attracts scientists from around the world interested in High Arctic studies.

Resolute Bay serves as a jumping-off point for expeditions to the North Pole, Quttinirtaaq National Park and various Franklin Expedition tours. It remains home to the ancient glaciers and vast stretches of unpopulated Arctic landscapes.

History

In the nineteenth century, no Inuit were permanently living on Cornwallis Island. European explorers passed by the island during searches for the Northwest Passage. The island remained uninhabited until a joint US-Canadian weather station was set up in 1947 and a Royal Canadian Air Force base was created in 1949.

Resolute Bay’s history as a modern Inuit community began in the 1950s when the Government of Canada relocated families from Pond Inlet, who call themselves Mittimatalingmiut or Tununirmiut, and families from Inukjuak, Quebec, known as Itivimiut, to the area. Afterwards, others moved to Resolute Bay from Pond Inlet and Inukjuak to join family and friends who had been part of the relocations. By 1961, the combined Inuit population in Resolute Bay had reached 153, with a constant presence of a large transient Qallunaat (non-Inuit) population (sometimes more than 300) associated with the airport and related facilities. This caused tensions within the community, while also providing employment opportunities for Inuit.

Unlike other Inuit communities, people in Resolute Bay had to adjust to the fact that there was no Hudson’s Bay Company post nearby. Instead, the government of Canada assumed responsibility for acquiring and shipping goods to Resolute Bay.

During the 1970s, Resolute Bay underwent significant change as it transformed from a supply base for Arctic military and weather stations to a major base for the shipment of personnel and equipment to remote drilling or mine exploration sites.

In 1975, the community itself was relocated to its present location, allowing better municipal services.

In March 2019, the Government of Canada issued a formal apology to Inuit for its actions on the Tuberculosis epidemic from the 1940s to 1960s. In August 2019, the Government of Canada formally acknowledged and apologized for its colonial actions and policies towards Inuit in the Qikiqtani Region between 1950 to 1975.

To learn more about the history of Inuit and the community of Resolute Bay, visit the Qikiqtani Truth Commission Community History.

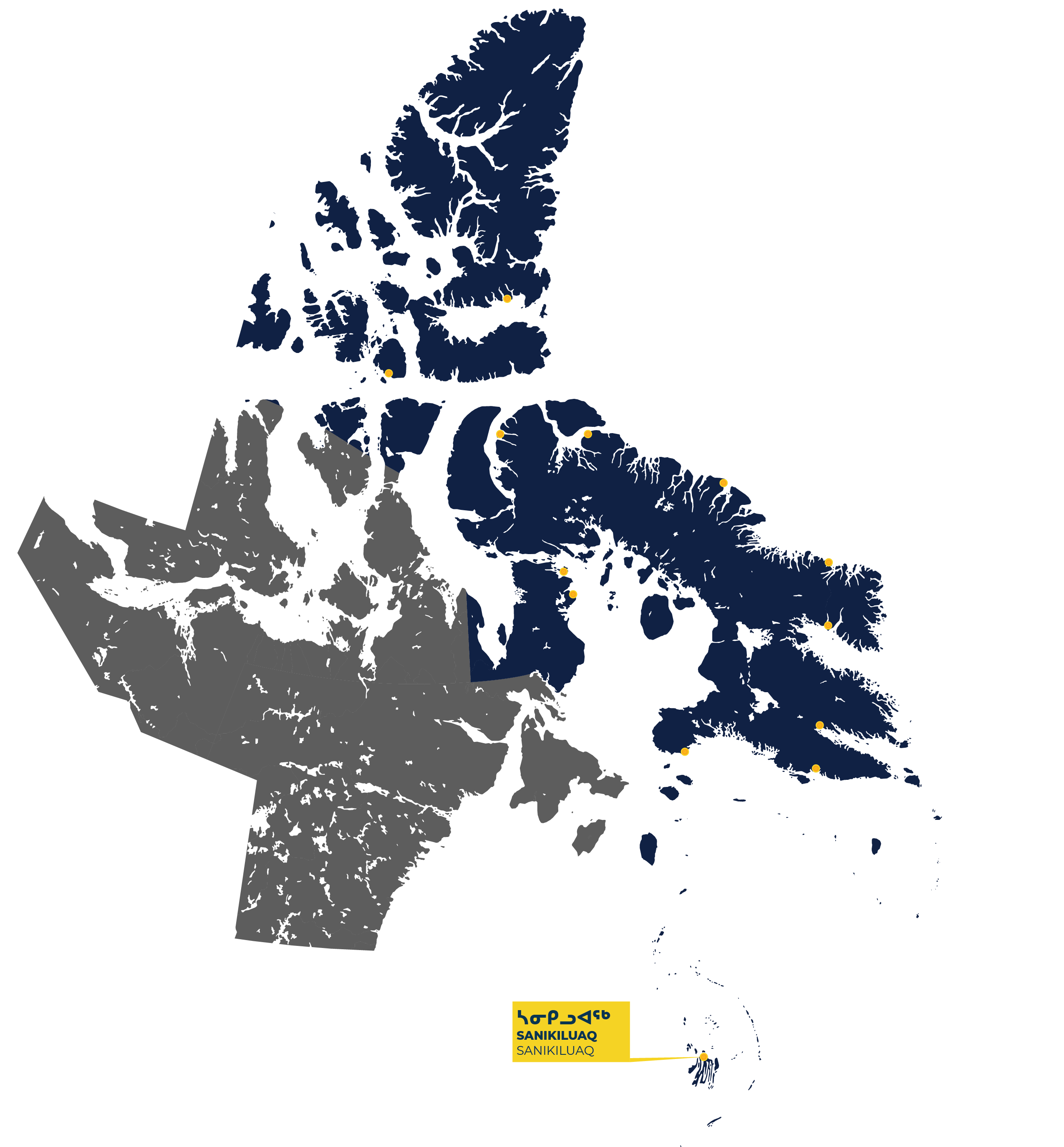

Sanikiluaq

1,010 Total Population

95% Inuit Population

92% Inuktitut Speaking

26 Average Age

15% Population with Highschool Diploma

Sanikiluaq is Nunavut’s southernmost community, located on the north end of Flaherty Island, the largest of the Belcher Islands in Hudson Bay. Sanikiluaq, which until 1975 was called North Camp, is named after the leader of an ilagiit nunagivaktangit that was located in the area. The people call themselves Sanikiluarmiut, meaning “people of the islands.” Inuit in the area lived in seasonal ilagiit nunagivaktangit, a place regularly used for hunting, harvesting and gathering. Inuit traditionally had several ilagiit nunagivaktangit, which allowed them to move to follow game

The archipelago of the Belcher Islands consists of numerous long, thin peninsulas and almost 1,500 islands divided by narrow straits of saltwater and speckled with countless freshwater lakes. Rock formations on the islands are studied by geologists who have noted that there is nothing like them in Canada. The sparse vegetation found on the islands includes lyme grass, which is used locally for handcrafted baskets.

Soapstone is quarried on Tukarak Island and is the basis of a successful local carving industry.

Rocky cliffs tower high above sea level near Sanikiluaq. These cliffs are nesting grounds for eider ducks, whose feathers are collected from the nests and made into warm outwear and bedding. Inuit families sustainably collect the eiderdown and sell it to companies who make parkas and duvets.

Just north of Sanikiluaq is Kinngaaluk Territorial Park, which contains archeological remains and provides space for camping and harvesting.

Today the population of this mainly Inuit community depends on an economy based on subsistence harvesting, fishing, soapstone carving, basket making, and tourism.

History

Sanikiluarmiut share a long history with Quebec Inuit. Until the early twentieth century, Sanikiluarmiut travelled great distances to the Ungava region of Quebec to trade at a Hudson’s Bay Company post.

For most of the twentieth century, the people of the Belcher Islands numbered less than two hundred. Following the disappearance of the islands’ caribou herd during a particularly difficult winter, Sanikiluarmiut learned to use eider ducks, which live year-round on the islands, as a source of food, clothing, and materials.

After being sent to the Belcher Islands to investigate trade and mineral possibilities, the HBC opened a seasonal post in 1928. Four years later the RCMP began regular patrols of the area.

By the 1950s, Sanikiluarmiut were not yet on the brink of a period of externally driven social or technological change. With limited contact with HBC and southern officials, they still relied heavily on locally available resources.

In the mid 1950s, Canadian officials considered whether everyone in the Belcher Islands should be forced or enticed to move off the islands, or if a townsite should be constructed on the islands. Schooling had become an extremely high priority for southern administrators and therefore planning for a school in the Belcher Islands began around 1956.

In 1956, an epidemic of whooping cough, which many have been spread by exposure to nearby iron ore miners, afflicted 80 per cent of the Inuit living nearby. During this time, about half of the qimmiit (sled dogs) were killed for food because men were too sick or unable to hunt. Many family members were evacuated for medical treatment in a southern province.

By the end of the 1960s, the school, an Anglican church, a small co-op, and a power plant served as a focus for a settlement. In 1970, the government consolidated all services and moved everyone to Sanikiluaq, at the north end of the islands. Because of an increase in population, officials began a strict enforcement of loose qimmiit, resulting in many sled dogs being killed.

Sanikiluaq became a hamlet in 1976 with a population of 295. Today almost 900 people live there. Sanikiluarmiut have found various ways to build lives and businesses on the Belcher Islands, while sharing the vast knowledge of a remarkable environment with the world.

In March 2019, the Government of Canada issued a formal apology to Inuit for its actions on the Tuberculosis epidemic from the 1940s to 1960s. In August 2019, the Government of Canada formally acknowledged and apologized for its colonial actions and policies towards Inuit in the Qikiqtani Region between 1950 to 1975.

To learn more about the history of Inuit and the community of Sanikiluaq, visit the Qikiqtani Truth Commission Community History.

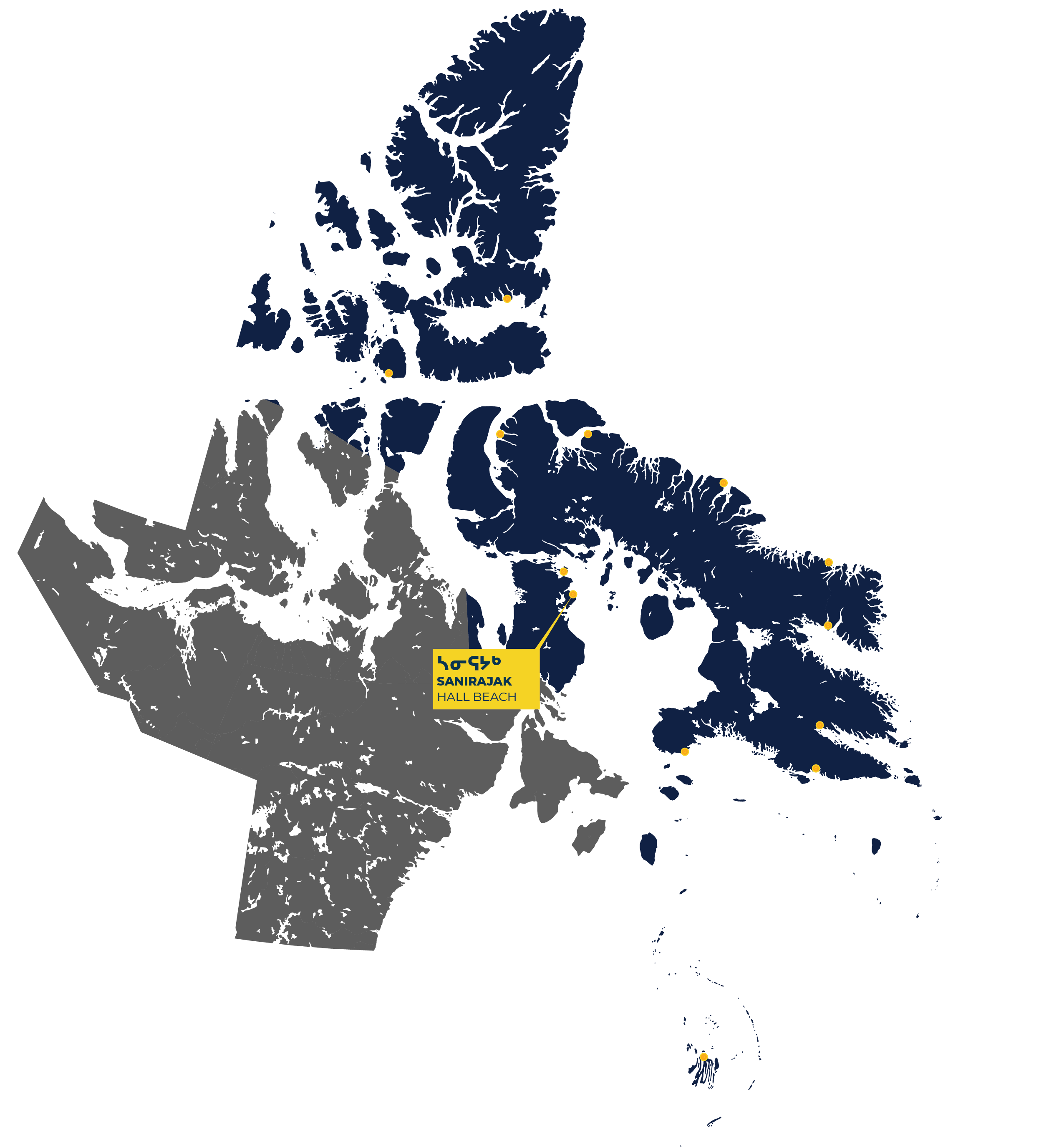

Sanirajak

891 Total Population

96% Inuit Population

95% Inuktitut Speaking

24 Average Age

10.7% Population with Highschool Diploma

Sanirajak (temporarily known as Hall Beach), meaning ‘the shoreline’ in Inuktitut, is the oldest known permanently inhabited community north of the Arctic Circle.

Sanirajak sits on the shoreline of Melville Peninsula on a long, flat beach located on the western shore of Foxe Basin. Two significant sea currents flow into Foxe Basin. This results in loose sea ice packing huge areas of the basin each year. New ice forms during the month of October and by November Foxe Basin is completely iced in. The ice starts melting in May or June, but it is not until August that it begins to rapidly disintegrate.

Today, Sanirajak is a community of over 800 people. The area is abundant in marine life including walruses and beluga whales. Harvesting has been vital to the region, before and since the establishment of the community. Harvesters not only contributes to the food security of all community members but also reaffirms Inuit culture and maintain a strong connection to the land.

History

For thousands of years, the region was home to numerous multi-family groups whose traditional territory had abundant marine mammals and other food resources. Inuit in the area lived in seasonal ilagiit nunagivaktangit, a place regularly used for hunting, harvesting and gathering. Inuit traditionally had several ilagiit nunagivaktangit, which allowed them to move to follow game. Prior to centralization, Inuit in the region moved around the area, congregating at various points during the year.

The first documented visit by Europeans to Foxe Basin was in 1822-23, when two English Royal Navy vessels sailed into the basin. Later, in 1867 and again in 1868, American explorer Charles Hall traveled to the area to investigate the fate of the missing Franklin Expedition.

The Hudson’s Bay Company opened its first trading post in Foxe Basin at Igloolik, 70 km north of Sanirajak, in 1939. The establishment of a store in the region meant that people could visit the post more often, no longer having to make the long sled patrols to Pond Inlet or Naujaat.

In 1955, when the Cold War resulted in the establishment of a chain of Distant Early Warning (DEW) radar sites, the southern part of the region’s annual routines were transformed when a site was established at Sanirajak.

By 1958, Inuit had gathered in two large new settlements near the DEW Line station. The federal government initially resisted providing services here to Inuit. They reluctantly provided houses, a civilian nursing station, and finally a school in 1967 in the settlement. Between 1950 and 1975, Sanirajak faced many hurdles in obtaining access to services as the federal government generally viewed the settlement as a support unit for military and transportation installations and not as a community.

The RCMP, for instance, only established a detachment in Sanirajak in 1987, despite repeated requests from the community for a police presence.

In March 2019, the Government of Canada issued a formal apology to Inuit for its actions on the Tuberculosis epidemic from the 1940s to 1960s. In August 2019, the Government of Canada formally acknowledged and apologized for its colonial actions and policies towards Inuit in the Qikiqtani Region between 1950 to 1975.

To learn more about the history of Inuit and the community of Sanirajak , visit the Qikiqtani Truth Commission Community History.